![]()

One of the bigger personal projects I’ve been working on recently is my Cinematic Studio Lighting course. During the process of writing the accompanying notes and shooting promotional images for the event, I’ve done a ton of research on how cinematographers and directors of photography work, think, and plan their shots.

Warning: This article contains photos that may not be safe for work.

I originally thought the two worlds of photography and cinematography would be fairly similar, but I ended up learning a lot more than I thought I would and I think that’s down to how cinematographers approach the setup of their image compared to many of us photographers, especially those of us who primarily shoot in a studio.

As portrait photographers, the subject takes center stage. Everything revolves around the subject looking their best and although we consider the background, it will always take a backseat over our primary goal of making the subject look perfect.

This idea is often reversed in cinema as the background and environment take the lead. The scene needs to look believable, lived-in, and real. The subject is obviously important, but they have to exist within the environment you’ve created. You can’t light a late-night bar scene believably and naturally, only to have your subject lit perfectly with three-point lighting. It would look ridiculous, nobody would believe it’s a real place and the viewer is kicked out of the immersion.

So with this bigger picture approach to lighting in mind, let’s now look at 5 key aspects of cinematic lighting that we can learn from cinematography.

Note: The following article is just one of the chapters from my workbook of notes for my new Cinematic Studio Lighting course and if you’re interested, for context, here’s a link to what I am teaching at the event: Cinematic Studio Lighting.

Below I’ll share pages from my book and elaborate on certain elements I refer to. Everyone at the workshops will obviously get my entire workbook of notes as part of the event.

5 Aspects of Cinematic Lighting

What defines a ‘cinematic’ image and what can we do as image-makers to try and capture the essence of a ‘cinematic shot’?

1. Depth

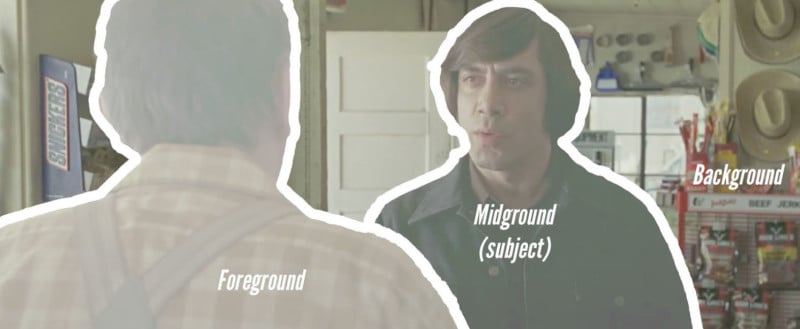

Think about the key layers of interest to your shot.

Consider the foreground, subject, and background and what part they play in the shot as a whole. What light does each of them need and where do you want the viewer to look within that scene? Don’t forget that lens choice and apertures will play a huge role in depth too.

Leading your viewer into a scene is something we should do more of as photographers and ordinarily, we’re very wary of having anything in front of our subject. But as long as the foreground isn’t fighting for attention with our subject, nor is it obscuring anything important, it can add a huge amount of interest to the shot, especially in a studio shot. The reason for this is because we as the viewer are drawn into this artificial depth. I say artificial as it’s still a 2D image, but we’re adding the illusion of a 3rd dimension with forced depth.

As I mentioned above, be sure to consider the lens length and aperture when looking to add depth. As a guide though, a longer lens (e.g. 85mm, 105mm) with a shallower aperture (f2.8, f1.8) will often give you a strong sense of depth with your subject in the middle.

Here are some examples of adding depth into your photos:

If you’re looking to add depth to your shot, be sure to consider the following:

- Foreground

- Mid-ground (subject)

- Background

- Contrast between them

- Focal point (viewers attention)

- Lens length

- Aperture

2. Shape & Form

In portrait photography, I break a subject into ‘shape’ and ‘form’.

The shape is the subject’s outline (silhouette) or their contrast against their surroundings, and form is the 3D structure light gives to the subject to show depth on them. In cinema, we have to apply that same principle of shape and form to not only the subject, but the foreground and background as well, we just need to be more mindful of how much of each we give them.

In cinematography, we have to account for the background and foreground as well as the subject and we need to make a conscious decision on how much shape and form we give the less important aspects of our scene.

Ordinarily, our subject is the key feature so we need to make sure we show a lot of shape and form on them, whilst allowing for the less important layers to have less.

Take a look at one of the great masters of cinematography today, David Fincher. Fincher isn’t known for his bold strokes in color and although there are exceptions to this, he often shoots his films either at night or in very dark locations. As a result of this, he is an absolute master of manipulating shape and form in his predominantly dark films.

One of the best examples of this is in his 1995 film ‘Se7en’. Again, most of this film is shot in dark, dingy apartments or in subdued, raining, outside light. Almost all of this film is shot with carefully placed lighting and even in scenes with windows in them, they are rarely allowed to light the actual scene.

Take a look at the office scene below where we see impeccable lighting throughout a very detailed shot with a lot of depth and including multiple layers of foreground and background. Pay careful attention to how the important aspects have a lot of shape and form and how less important elements have very limited form.

See how we have multiple foreground and background layers? See how the deep foreground and deep background don’t really have any form to them whatsoever? The black boxes in the foreground are just dark shapes and the widow blinds behind are the same.

Let’s break it down visually and see how they’ve managed to light what could have been a very visually busy and complex scene.

![]()

Breaking your shot down into layers like this can help you to visualize what’s important in the scene and what’s simply there to help sell the story within it. Make sure your subject has a lot of shape and form and then try to ensure other aspects of your image have less form to them. Doing this allows the extra detail that form provides on the subject to draw your viewer’s attention.

Truth be told, this is far easier-said-than-done, and to do it at the same level as directors like Fincher requires a lot of experience, time, and kit. I personally rarely shoot on location, but in the studio I can keep it incredibly simple whilst still applying these same principles. Take a look at some examples of what I mean below.

Here are some examples of shape and form within photos:

When considering Shape and Form in your shot, be sure to include the following:

- Ensure a clear shape around your subject against the background

- Draw the viewers focus by ensuring the subject has a lot of form from the lighting

- Think about the layers in your shot and how the light should be on each of them

- A darker foreground and background is an easy way to make your subject more pronounced

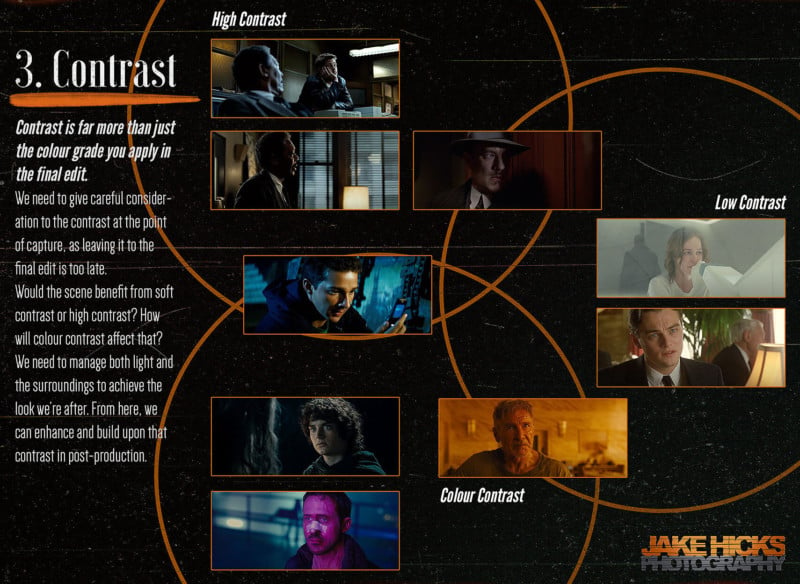

3. Contrast

Contrast is far more than just the color grade you apply in the final edit.

We need to give careful consideration to the contrast at the point of capture, as leaving it to the final edit is too late.

Would the scene benefit from soft contrast or high contrast? How will color contrast affect that? We need to manage both light and the surroundings to achieve the look we’re after. From here, we can enhance and build upon that contrast in post-production, but only if the foundation of light was captured, to begin with.

Below you’ll find one of the pages from my Cinematic Studio Lighting workshop workbook as an example of some variations of contrast found in cinema.

Next time you’re watching a film, pay close attention to the mood of a scene and then look at the contrast being used within it to see how that mood is being bolstered by the lighting. This is a general guide, but usually high-contrast scenes will have drama, tension or action unfolding, and low contrast scenes tend to be slower, have longer exchanges of dialogue, or are simply trying to represent a more believable natural environment on screen.

Like it or not, modern cinema now heavily relies on bold color contrasts in their films as well. Big-budget movies that want you to view it in 8K wowo-vision don’t tend to have a lot of bold contrast as every pixel contains masses of data. To combat this, color is used to great effect as a way to guide the viewer, and although they’re far from good movies, the seemingly endless supply of superhero movies in recent years do use color contrast very well in this way. (You have over 55 superhero movies from the last 20 years to choose from! I hope you’re ready for those films from 20 years ago to start being remade!)

Bringing it back to photography though, we need to be applying the same mindset with how contrast in our shots can affect the final look too. One last element I want to clarify about contrast is the idea that hard-light always equals hard-contrast. Yes, this can be true, but try instead to think about contrast has how much light the shadows have. Below are two images, on the left (the orangey one in case you’re viewing it on mobile) I’m using a very soft-light modifier and on the right (red styling) I’m using a very hard-light modifier, yet the contrast is similar due to how much light they both have in shadows.

Here are some examples of various contrasts in photos:

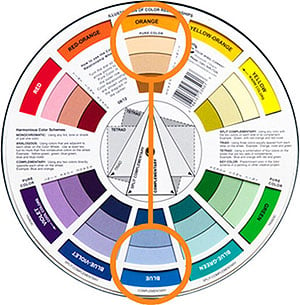

Contrast also applies directly to color too and a little knowledge of the color wheel and a basic grasp of color theory will help you here as well.

For example, an image can have contrast even if all lights within the image are the same exposure thanks to ‘color-contrast’. Take a look at the color image below and then look at that exact same image in black and white next to it.

color contrast and using color theory to achieve it is an entire article in its own right, so although I won’t do a deep dive on it here (plus there are already loads of articles on my site regarding this subject already). Here are a few pointers to get you started.

Complimentary colors will give you the most color-contrast when using 2 colors and these are the colors opposite one another on the color wheel. Yes, you guessed it, orange and blue are the most popular complementary colors in cinema. From here, it’s really any color furthest from one another on the color wheel when adding multiple colors in the same scene. So for 3 colors like the image above, consider the triadic color theory, for 4 colors look for tetradic colors, and for 5 look at tertiary colors.

When considering contrast in your shots, remember to think about:

- How will contrast affect the mood of this shot?

- Do I want high or low contrast?

- Contrast is not just the lighting modifier you use, but the amount of light in the shadows.

- Contrast in an image can be achieved purely by using contrasting colors.

4. Motivation

‘Motivation’ speaks to ‘motivated light’.

This is actually far less prevalent to studio shooters like me, but it’s always of the utmost importance in every movie and it’s an extremely useful skill to have if you’re shooting on location or simply wanting to understand light better in general.

So what is ‘motivated light’? Motivated light refers to where the light is ‘supposed’ to be coming from in the scene to make the shot look believable to the viewer. For example, If we see a zoomed-in shot of someone sat down at a table with very little context, yet they are lit with a very bright warm light to camera left, it feels odd. If we then show a wider shot that includes a table, a cereal bowl, and a large window to camera left, our brain immediately puts the scene together as a breakfast table and the warm bright light is now accepted as beautiful early morning light.

The trick here comes in that the window may not be the actual light source in the shot, the subject may in fact be lit from a giant scrim and color temperature orange gel, but the viewer never questions that because we saw the window.

This is what the vast majority of lighting on film sets deal with and it’s actually a great way to plan your lighting in general. The goal is always to make the shot look visually engaging, yet still believable and each light in cinematic lighting has to have a purpose. What is this light adding to the scene? If it’s not adding anything, it really needs to be removed.

Like I mentioned above, motivated light is about making a scene ‘believable’. In a studio, if I wanted to make someone look scary, I’d light them from below and that’s it. I wouldn’t need to show the viewer where the light was to make it believable yet in cinema, they don’t get that luxury and if they want to light someone from below, they essentially have to show their workings.

Take a look below at another example from my Cinematic Studio Lighting workbook.

Lighting from below is often used to make the subject look scary or menacing. It’s also very obvious and can look awkward if not done well. Here, the bad guy on the bed is lit from below yet we don’t question the lighting because we can clearly see the light source in shot. This is motivated light and you can get away with almost any lighting, as long as you make it believable in the context of the scene.

Take a look at another example of motivated light here from David Fincher’s 1995 film ‘Se7en’.

![]()

Many lighting setups are trying to light the scene and the subjects at the same time. On film, this actually requires a lot of light, and more often than not, you need to have a lot more lights on set than in your actual shot.

Here we have a ‘motivated’ light on the left in the form of a lamp, but there’s actually a lot more lights involved to illuminate the subjects clearly.

One of the other reasons it’s hard to light the subjects with lights in the actual scene is that they’d need to be very bright to do so. This would then result in this lamp being extremely blown out in shot and distracting.

Sometimes, motivated lights may even be out of place in reality, but in the flow of a movie, they go unnoticed yet still do their job of motivating the light in the scene.

Here in Todd Phillips’ 2019 film ‘Joker’, we see a small office scene.

![]()

The back corner of the room was obviously very dark in the shot, so rather than have it drop off to black, they’ve added a small desk lamp back there to fill in some of those heavy shadows.

There’s no real reason to have a random lamp on in the back of the room here, but it’s still better to do that than it is to throw supplemental light back there from a crew light that would be out of shot. Motivating the light in the scene is extremely crucial in cinema and you’ll find odd lights placed in films to fulfill this desire to make the light believable to the audience as their immersion is key.

Here are some examples of motivated light within photos:

In the above shot, I’m using a section of a London nightclub that has these interesting hanging ambient lights. As in most nightclubs, the lights are very dim, so I’ve augmented the look with not only an orange light coming through onto the model, but I’ve also added an orange light in the room behind her to illuminate that section behind her as well.

The motivated lights I bring along to location shoots are often just tungsten bulbs and when combined with flash in a shot, they’re actually not that powerful. As a result, the model light is ‘motivated’ by that globe, but in reality, she’s being lit by another flash out of shot. You need to be careful when doing this though as you can’t stray too far from where the motivational light is.

When using ‘motivated’ lights in your shot, be sure to consider the following:

- If shooting on location, would this lighting be believable to the viewer?

- If it’s not immediately believable, can we add a motivational light in the scene to help?

- Use motivational lights to add interest and depth to a shot?

- If the motivational light isn’t lighting the subject directly, be sure to add believable additional lights out of shot.

- When adding lighting to compliment the motivated light, don’t stray too far from where that light is coming from.

5. Atmosphere

Atmosphere or ‘volumetric light’ can quickly give you that cinematic look, but you need to be careful and purposeful with how you use it.

In the context of this article, atmosphere refers to the actual air or look of the air in the scene. This is often easily achieved in cinema with fog and haze machines, but care needs to be taken to not overdo it. Yes, haze looks cool, but it may look a little out of place to have thick casino smoke with god-rays pouring through the windows at a 4-year-old kid’s birthday party. Again, what is motivating that atmosphere?

Adding fog, haze or other forms of smoke to your shot can dramatically change the look of the image by enhancing the depth within the frame. We’ve already established how important depth is to a shot, but by adding atmosphere to that, we can further guide our viewers to where we want them or say something extra about the subject.

Atmosphere doesn’t stop with physical particles in the air either, as we can even add lens filters or even post-production atmosphere to further get the desired look we’re after as well.

Here are some of the main ways we can add atmosphere to our scene:

1. Fog

There are a few key differences between fog and haze, but primary among them is the shape and texture of fog. Fog is far thicker in shot and is often used to light outdoor scenes as it will hang in the air longer. Fog machines are fairly cheap to buy and run too.

2. Haze

Compared to fog, haze appears far finer in shot and doesn’t clump and swirl like fog can. Thanks to this, haze is primarily used indoors to add volume to the light without dominating the scene. For indoor photography, I’d have to recommend haze every time, although the machines can cost a little more.

3. Motivated Atmosphere

Sometimes, heavy haze indoors can look odd and out of place, even if it looks visually good in shot. By adding a reason for the atmosphere, like someone smoking or a fireplace, the haze immediately feels more natural and can ofter allow you to add more of it without it being distracting.

4. Lens Filters

Many cinematographers will try to soften a sharp, modern digital image with lens filters. This technique is especially useful when filming a period piece where an overly crisp or sharp image can feel out of place for the time. Many brands make a variety of filters like this and they come in a variety of strengths depending on the look required.

5. Post-Production Atmosphere

Although you may have used fog or haze at the point of capture, you can add further drama and atmosphere with lens flares in post. This look has fallen a long way out of favor at the moment though, so I would be very cautious of using the post-pro method unless the scene really benefits from it. Instead, I would urge you to capture more believable flares in-camera with lenses and filters.

Here are some examples of atmosphere in photos:

When looking to add atmosphere to your shots, be sure to consider the following:

- Add fog for a far more dramatic effect or to hide background elements.

- Use haze for a very subtle and less distracting look.

- If you want a lot of smoke or haze in your shot, can you add a motivation to the scene to provide an excuse for it to be there.

- Make your modern digital images a little more organic to look at by using a subtle lens filter.

- Add post-pro atmosphere and flares sparingly. Always try to achieve those looks in-camera to make them believable.

Some Closing Thoughts…

Obviously, cinematography learns a huge amount from the photography world, especially where lighting is concerned, but in turn, I think we as photographers can learn a huge amount from cinematography as well. Yes, many of us may only work in the studio and yes, much of our lighting must be fully focused on making the subject look their absolute best and not necessarily prioritize the room they’re in, but I still think there is room for us to consider adding another layer to our lighting.

By all means, light the subject beautifully, but how can you maximize depth within that shot so as to draw the viewer in? Yes, the subject is lit well, but do they stand forward of their surroundings? Is their black jacket getting lost against a dark corner of the background? Can we use contrast in this portrait to really make the image pop? Is heavy contrast needed, or do we want a softer contrast to suggest a more demure mood to the image? What about color? Can we use contrasting colors as well as light and shadow to push engagement?

Also, be sure to consider the story or motivation behind the shot. Can we add some believable warmer colors to the image if we include a lamp in the background? Can we cool the image down by placing them by a window and playing with the white balance? And lastly, can we add some atmosphere to the shot? Sure the studio may be cool, but is it feeling a little too clinical and un-lived-in? Perhaps adding a little haze to the shot will keep the focus on the subject and less on their surroundings.

It goes without saying that there’s a lot to consider here, but I think it’s all of these little extra cinematic elements that can take a potentially good image to a great image with only just a little thought.

If you’re interested in learning more about other aspects of cinematic lighting, including film-set lighting setups and set designs you can use in your own portrait photography, then by all means check out my latest lighting course ‘Cinematic Studio Lighting’.

About the author: Jake Hicks is an editorial and fashion photographer based in Reading, UK. He specializes in keeping the skill in the camera and not just on the screen. If you’d like to learn more about his incredibly popular gelled lighting and post-pro techniques, visit this link for more info. You can find more of his work and writing on his website, Facebook, 500px, Instagram, Twitter, and Flickr. This article was also published here.

No comments:

Post a Comment